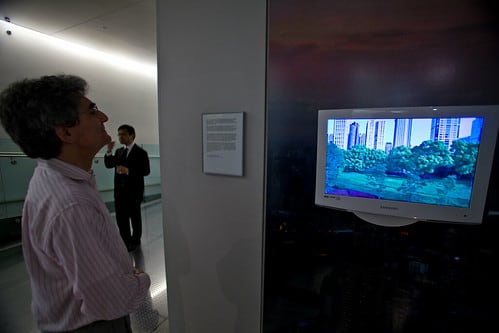

Pictures from the opening of the China Prophecy: Shanghai exhibition in the New York Skyscraper Museum.

On June 24 2009, The Skyscraper Museum in New York City opened China Prophecy: Shanghai, a multi-media exhibition that examines Shanghai's evolving identity as a skyscraper metropolis. Featuring models of the major iconic structures, including Jin Mao, Tomorrow Square, Shanghai World Financial Center, and the new super-tall Shanghai Tower, as well as computer animations, film, drawings, and historic and contemporary photography of the city, the exhibition combines an in-depth look at the new generation of towers with an overview of the sweeping transformation of the city’s traditional low-rise landscape into a city of towers.

China Prophecy: Shanghai, which runs through March 2010, concludes the Museum’s three-show series FUTURE CITY: 20 | 21 that has examined parallels in the rapid urbanization of New York, Hong Kong, and Shanghai in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

Shanghai today is a vast metropolis of 18 million residents–the largest city in the world’s most populous nation. In just three decades, its population has nearly doubled, and the city has been physically transformed by the twin emblems of modernity–high-rises and highways. Formerly a horizontal expanse of dense and sprawling lilong neighborhoods, Shanghai has grown vertically. Nearly 400 high-rises of twenty stories or more were built in the historic core, Puxi, since 1990, and colossal elevated roads fly over old neighborhoods. In the new business district of Pudong on the east side of the river, a master plan dictates taller towers rising from open green space, culminating in a pair–soon to be a trio–of the world’s ten tallest skyscrapers.

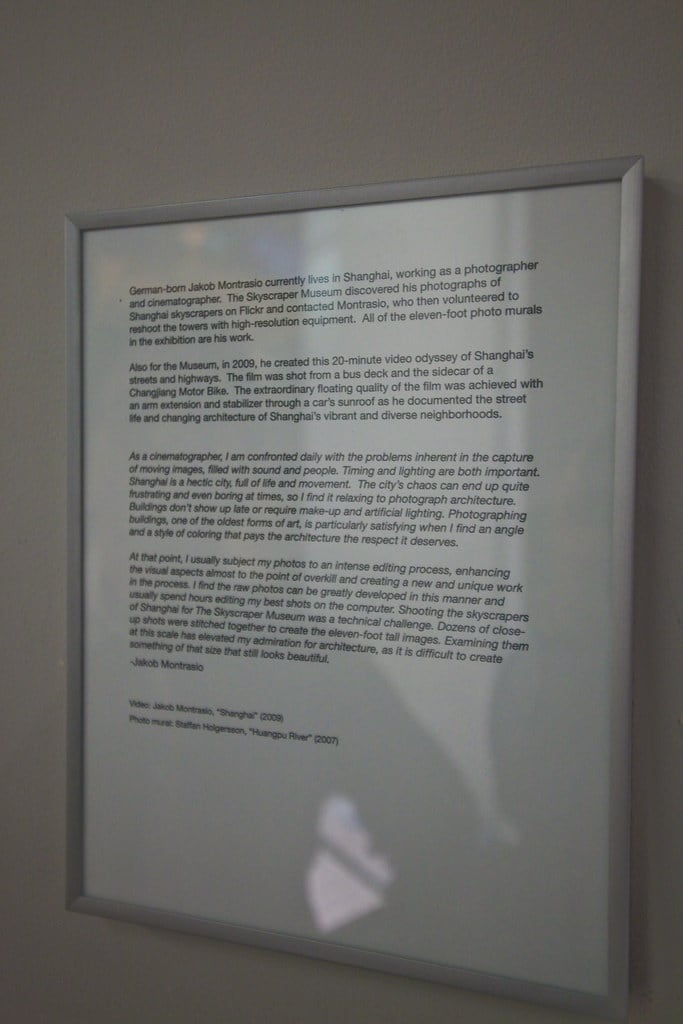

The exhibition China Prophecy: Shanghai documents this stupendous urban transformation through film and photographs of old and new Shanghai, including a 20-minute video odyssey traveling the city’s streets and highways filmed by resident director of photography Jakob Montrasio. Evoking the speed and ambition of the city’s futuristic focus are projected computer animations by the Chinese company Crystal CG that create spectacular flyovers of the city before circling the major skyscrapers that are their subjects.

The installation features large models of the major towers that now define–or will soon enhance– the Shanghai skyline. These include an architectural and wind-tunnel testing model of Jin Mao (88 stories; 1999); a presentation model of Tomorrow Square (55 stories; 2003); a massing model and structural engineering model of the Shanghai World Financial Center (101 stories; 2008); and an architectural model and structural computer models of Shanghai Tower (128 stories; 2014), now in development. Other renderings, sections, and construction photographs illustrate a range of technical issues that distinguish these towers, which are all designs of American–and mostly New-York based–architectural and engineering firms. Other major high-rise projects included in the exhibition are KPF’s Jing An complex and SOM’s White Magnolia Plaza, both in development. The issue of global design practice is explored in the exhibition and a related lecture series in fall 2009.

These new Shanghai super-skyscrapers are ambitious in their height and innovative engineering. At 1380 ft. (438 meters), Jin Mao, designed by the Chicago office of Skidmore Owings & Merrill, is taller than the Empire State Building; the Shanghai World Financial Center, designed by New York-based architects KPF, is taller than any U.S. skyscraper at 1614 ft (492 meters); and Shanghai Tower, designed by the American firm Gensler, has an announced height of 2073 ft (632 meters), which will make it the tallest building in China and the second tallest in the world. Typical of these Shanghai towers, as well as those being built today throughout Asia and the Mideast, is a mixed-use program that includes a commercial base, zones of offices, residences or luxury hotels, and restaurants and observation desks on the top floors. The concept of the structure as a “vertical city” is often invoked–offering parallels to early twentieth-century visions of New York as the city of the future.

Sustainable skyscraper design seems an oxymoron to some, but as the exhibition argues, high-rises and high density–in conjunction with mass transit–is a logical strategy for greener cities. The city’s most advanced high-performance design planned to date is the double-glass curtain wall of the Shanghai Tower, which will encircle eight stacked 15-story segments with atrium spaces and sky gardens soaring the full height of the 128-story structure. “Better City, Better Life,” calls out Shanghai’s emphasis on sustainable design as the slogan for the 2010 Expo, which will open May 1, 2010. The exhibition illustrates the Expo in plans, photographs, and a Crystal CG animation of the site and pavilions that emphasizes Shanghai’s self-image as the city of the future.

Three major approaches to urban planning and design are evident in Shanghai today and illustrated in the exhibition. In the historic core Puxi, high-rise commercial and residential development proceeds by razing individual sites or whole low-rise neighborhoods in a patchwork process–either for single skyscrapers or for major mixed-use projects on a mega-block, such as Plaza 66 and the future Jing An complex. The second, radically different approach governs the growth of Pudong, the expansive new area of development on the east side of the Huangpu River, a district that extends to the East China Sea and covers 200 square miles (about half the size of New York’s five boroughs). The name Pudong is commonly used as shorthand for the concentrated skyscraper district, Lujiazui, the Finance and Trade Zone that has developed as Shanghai’s new center for international business. Stimulated by the government’s master plan in 1990, towers have grown as fast as bamboo on land that was principally agricultural or industrial waterfront. Lujiazui, an area the same size (and, indeed, shape) as lower Manhattan, now boasts more than three dozen skyscrapers of 40+ stories, including the 88-story Jin Mao and the 101-story Shanghai World Financial Center. The premise of the Pudong master plan requires open green space surrounding the towers and broad axial avenues that privilege cars over pedestrians. The result is a tower-in-the-park approach that stands in stark contrast to the dense, street-oriented development of Puxi. Historic preservation and adaptive re-use is the third approach to urban planning and design now being practiced in Shanghai. Featured examples in the exhibition are Xintiandi and the North Bund development, Rockbund.

Futurism and Vertical Cities: New York, Hong Kong, and Shanghai

The scale and speed of Shanghai’s rise reproduces and even surpasses Manhattan’s historic ascent in the early twentieth century. As the world’s largest city in 1930, New York boasted a population of 7 million and nearly 200 skyscrapers–more than all other cities combined at that time. Today, as high-rises proliferate everywhere, Hong Kong holds the title with 7,200. Still ascending, though, Shanghai is surely China’s prophecy of the urban future.

It is possible to buy prints from the exhibition's Shanghai photographs here at ImageKind.

By Jakob Montrasio

By Jakob Montrasio